Artist Judith Romney Wolbach is a relative late-bloomer when it comes to the scene, embracing art-making only after retiring from her legal practice at age 65. But in Wolbach’s case, inactivity in the arts was the sign of deep roots sifting through a diversity of experiences before breaking forth. Never formally trained in art, Wolbach yet brings over 75 years of diverse knowledge and experience to her craft… although the road was most certainly long, and surprisingly winding.

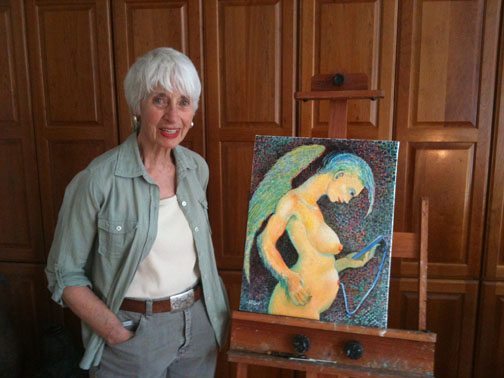

Judy Wolbach with her current work-in-progress.Born in Salt Lake City during the depression, Wolbach had an interest in art, among other subjects, from an early age. She was encouraged, perhaps a little too strongly, by her parents, to the point of picking out her major and future career in collusion with her high school guidance counselor. “I wasn’t there, of course,” says Wolbach.

Judy Wolbach with her current work-in-progress.Born in Salt Lake City during the depression, Wolbach had an interest in art, among other subjects, from an early age. She was encouraged, perhaps a little too strongly, by her parents, to the point of picking out her major and future career in collusion with her high school guidance counselor. “I wasn’t there, of course,” says Wolbach.

I had a broad range of interests that made it hard to make up my mind about what I wanted to do. I started worrying about it young: my parents had strong expectations. I was interested in art, and so I was able to take painting classes over at the old art center. I remember saying something like “Maybe when I grow up I’ll be a good painter” and my father replied, “You won’t be a good painter, you’ll be the best”, which was encouraging and also kind of frightening. Way back, when I left high school in 1953, my parents wanted me to be a medical illustrator, and since it was their idea, naturally, I didn’t do it.

The path was set for a wide-ranging career: Wolbach left behind her parent-approved double major in pre-med and fine art at the U in order to earn a bachelors in English from University of California, Berkley. Returning to Utah in the 60s as a single mother after the dissolution of her marriage, Wolbach taught high school, planning to get a masters in education… until she began taking the classes and found them unendurably dull. Instead, she switched to her minor, anthropology, earning her masters under Charles Dibble, one of the foremost Mesoamerican scholars. (Dibble was involved in the 30-year project to translate The Florentine Codex, a compendium of knowledge about the Aztec civilization compiled around the time of the Spanish conques, from Nahuatl into English .)

I was fortunate to be there when Charles Dibble was on the faculty, he was a brilliant man and I did a lot of my work with him. I got my masters degree, but I just knew that trying to get a position was not going to work out if I went on to get a PhD… so instead I went to law school! And why not? I’d been active in the anti-war movement and the ACLU, but I got really tired of arguing with people who dismissed anything I had to say because I didn’t have a degree in law. I graduate when I was 41. I married Robert Edminster, who was on the faculty in the economics department, and I practiced law for 24 years. I retired when I was 65, the year after my husband died. And two or three years after that, I discovered clay.

Left: Two “transitional animals” (with a friend procured during Wolbach’s travels.) Right: The large clay vessel has been dubbed the “polygamy pot”—”many handles for many hands,” says Wolbach.Wolbach, with her husband, is an avid collector of art, filling her walls over the years with works by Earl Jones, Mary Toscano, Don Olsen, and Sister Corita, among others. Although the collection was reduced Wolbach still has her first purchase as a collector, a small print of birds she bought in the ninth grade as a gift for her mother, who tacked it up in the family’s kitchen. Inspired by her anthropological studies and by her appreciation of the works, wasn’t until after her retirement that she began to immerse herself in the making end of art.

Left: Two “transitional animals” (with a friend procured during Wolbach’s travels.) Right: The large clay vessel has been dubbed the “polygamy pot”—”many handles for many hands,” says Wolbach.Wolbach, with her husband, is an avid collector of art, filling her walls over the years with works by Earl Jones, Mary Toscano, Don Olsen, and Sister Corita, among others. Although the collection was reduced Wolbach still has her first purchase as a collector, a small print of birds she bought in the ninth grade as a gift for her mother, who tacked it up in the family’s kitchen. Inspired by her anthropological studies and by her appreciation of the works, wasn’t until after her retirement that she began to immerse herself in the making end of art.

I was too busy, and got busier as time went on: the last five years of my practice I was a given a job as the first guardian ad litem in Utah, and it was very time consuming. Before that I took an art class here and there, but I didn’t follow through or do anything with it afterwords, so I didn’t have any kind of a body of work that I produced before I retired. The first thing that I did that really got me going was a class on Chinese ink painting. It was very, very helpful to me because I had to follow a lot of rules— I had to hold the brush a certain way, I had to make the marks in a particular way, and the subject matter was very, very limited. That helped me think about making some art again… because you have to be doing it before anything happens.

I happened to drop by a pottery studio in Sugarhouse, looking for a big black bowl to put on my dining room table. They didn’t have one, so I ordered one and while I was there I thought “this looks pretty interesting… maybe I should try my hand at it.” I’d never had anything to do with clay, and they tried to teach me how to use a wheel… and they couldn’t! I just couldn’t do it, so they suggested that I work in coils and slabs. They didn’t really teach that, but I hung around and used the facilities… and I became absolutely devoted to it.

I worked in the clay, and I worked in ink drawings, which really grew out of it. Then a couple of things happened. I broke my shoulder and couldn’t do anything for about four months, during that period of time the rhythm was broken: art is mostly in doing it, and if you do it sooner or later something is probably going to happen, and if you don’t, you don’t. I never got back into it in the way that I wanted to… and then I sold my house, and my kiln was there, so that was the end of it.

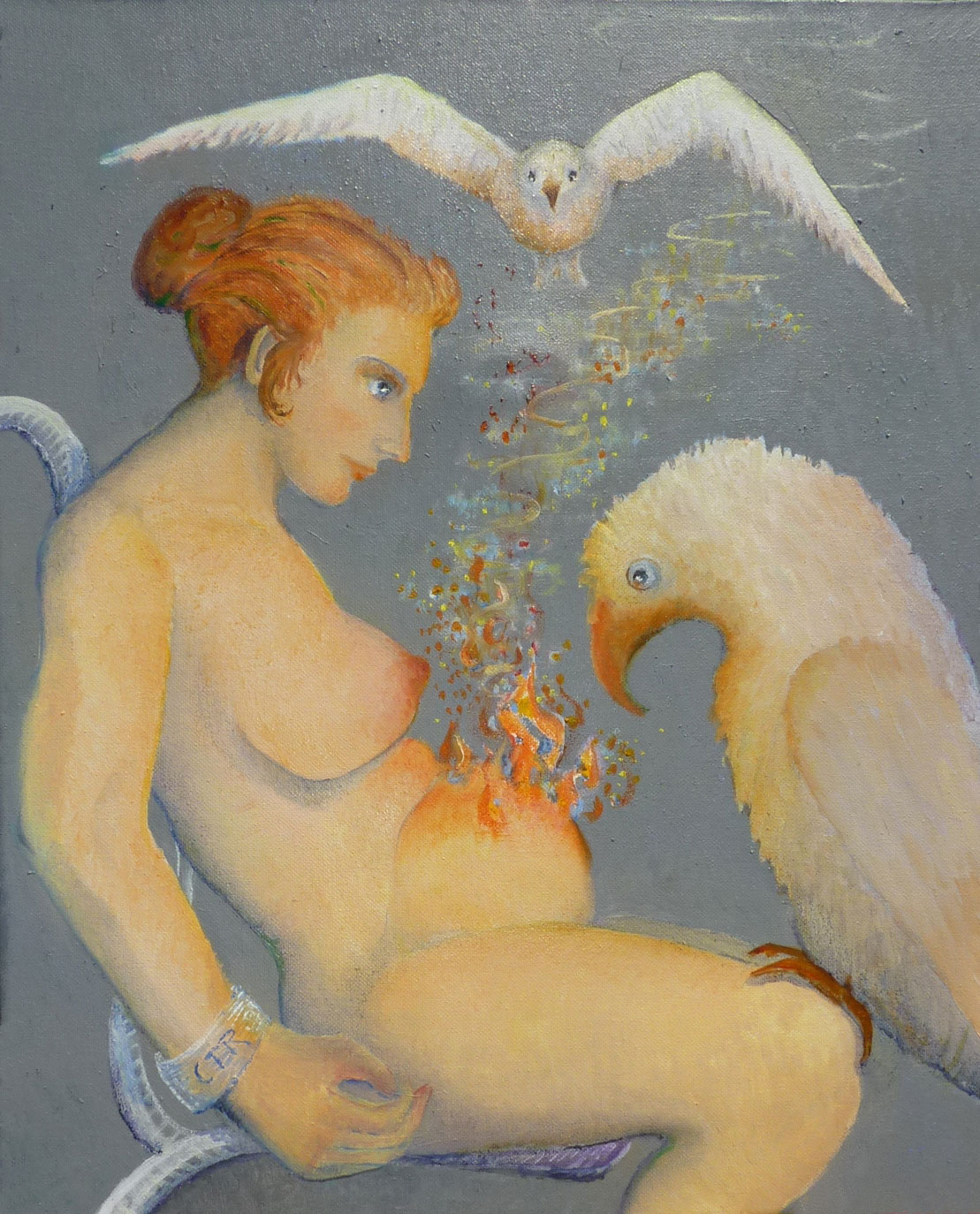

Oil painting from the latest series—”I started out with ‘the burning in the bosom,’ but ended up with fire in the belly,” explains Wolbach.But while Wolbach may have left behind one medium, she is currently cultivating another and adapting it to her style. One gets the sense in talking to Wolbach that she isn’t entirely happy or comfortable in her newest medium, but the same blend of restlessness and curiosity-driven can-do that has shaped much of her adventures is in evidence here, helping her strike a balance between accepting her limitations while continuing to push them.

Oil painting from the latest series—”I started out with ‘the burning in the bosom,’ but ended up with fire in the belly,” explains Wolbach.But while Wolbach may have left behind one medium, she is currently cultivating another and adapting it to her style. One gets the sense in talking to Wolbach that she isn’t entirely happy or comfortable in her newest medium, but the same blend of restlessness and curiosity-driven can-do that has shaped much of her adventures is in evidence here, helping her strike a balance between accepting her limitations while continuing to push them.

I feel very, very fortunate to be in a situation where I can do what I want to do, and I paint every day, at least six hours a day. It’s not always very productive, and I’ve thrown a lot of stuff away. Every Friday I go to the drawing session at King’s Cottage. I’m trying to build up my tool kit: that’s how I look at it.

I took live model drawing classes earlier this year, and then I realized that, frankly, at this point in my life I’m not going to be able to master that… some things are just not going to happen. I’ve accepted it, and I think thats why I’ve decided to revert to what I’m really good at, which is: imagination. I want to learn techniques so I can execute what I’m doing a lot better.

You don’t want to just be a mirror image of somebody else. I took three workshops from Paul Davis, and I really liked the portrait end of it, and he did have a procedure and a method that I thought was really interesting and it has helped me… but I like to paint or express something out of my own imagination or experience rather than a replica… cameras are really good for that, right? It’s been an interesting experience for me, because I really miss the clay; oil is a new medium, and I’ve been working in it for a little over a year, so I’m doing my best.

Her clay figures are clearly inspired by her travels and scholarship in Latin American artistic traditions. Eschewing color beyond the black or red clay, her pieces look like tableaus from unknown myths, with transitional animal forms that blend attributes of different species caught in the midst of inexplicable doings both playful and dark—the perfect attributes for mysterious forgotten gods.Her paintings are more colorful than her earlier clay and even pen works, they still have the same sense of mythos, remixed and media res, retaining some of the Aztec influence while mixing in LDS imagery. Her sense of humor and her willingness to tweak comes through in the abstract versions of Mormon temples or the Nauvoo sunstone, as she reappropriates the symbols of the religion to which she no longer belongs. The imagery is purely from her imagination, she says, in the grand Romantic tradition, and indeed you’ll find a similarity to William Blake’s paintings in some of her work. Wolbach will continue to develop her skills, and with Wolbach’s ability to reinvent herself, and embrace new talents and roles, we can only watch for her next transformation.

Judith Romney Wolbach’s oil paintings can be seen at the Charley Hafen Jewelers Gallery from August 17 through September 17, 2012. An opening reception with the artist will be held from 6-9p on August 17 during the Salt Lake Gallery Stroll. Her clay work can also be found in “500 Animals in Clay” available from Lark Books. More info about Wolbach and about her work can be found at her site.