An interview with Aiden Delgado: soldier turned Buddhist turned conscientious objector.

Intro and interview by Gina Edvalson.  Imagine yourself young and in college. You're not doing well. You need direction and structure, so you decide to join the Army Reserve. Ironically you sign the recruitment papers on September 11, 2001. The next thing you know your once-a-month commitment in the Reserve turns into full deployment in Iraq. And not just anywhere in Iraq – but a deployment as a mechanic at Abu Ghraib. What would you do? Who would you become? How would this experience shape you?

Imagine yourself young and in college. You're not doing well. You need direction and structure, so you decide to join the Army Reserve. Ironically you sign the recruitment papers on September 11, 2001. The next thing you know your once-a-month commitment in the Reserve turns into full deployment in Iraq. And not just anywhere in Iraq – but a deployment as a mechanic at Abu Ghraib. What would you do? Who would you become? How would this experience shape you?

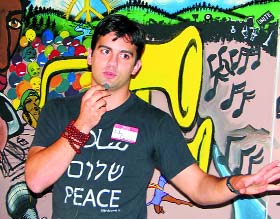

This is Aidan Delgado's story. He served with the US Army Reserves in Iraq and was honorably discharged in 2005. He is a now an active member of Iraq Veterans Against the War and the Buddhist Peace Fellowship. His new memoir is "The Sutras of Abu Ghraib: Notes from a Conscientious Objector."

Recently, KRCL community radio interviewed Delgado for its public affairs program RadioActive. Here is an excerpt from the interview.

RA: Talk about the day that you found out that you were going to Iraq.

AD: There had been ominous rumblings in the air for months. One day they called us all in formation and the commander strolled out in front of us and said, "You have three days to get your life in order, because we are all going to Iraq." Half the unit erupted in cheers and the other half started crying.

RA: What does that feel like?

AD: Honestly? It feels completely unreal. There is this sense of floating. I've described it as being tied to a stone – and someone throws the stone off a high precipice and for a moment it doesn't pull you because the rope is spinning out and finally it goes taut and you have this sensation of being dragged down. And that is what it's liked to be deployed in Iraq. There is that moment between here and there where you can just believe that you are safe, and then the stone pulls you down.

RA: And what did you start to think about the war?

AD: I had no conception of what it would really be like. When you're a kid all you've been exposed to is that war is glory and adventure. You know it's not true, you know it's not complete, but that was the place I was coming out of.

RA: And you knew some Arabic?

AD: True. My father was a diplomat. I had spent the last eight years of junior high and high school in Cairo, where I learned to speak passable Arabic, and that served me in Iraq.

RA: How did that familiarity inform your experience?

AD: It was absolutely transformative. When you have no sense of another culture and no sense of the regular rhythm of that culture, you live in a state of panic and fear all the time because it doesn't sound natural to you. You hear people speaking and it's only gibberish. You can't make out what they are saying. And having lived in Muslim society for almost a decade, going to Iraq was not an unfamiliar experience for me. So I was very much at ease. But my peers, most of whom had never left America, were terrified. They saw snipers on every rooftop and bombs around every corner.

RA: When did that start unraveling for you?

AD: It began relatively early. One of the things that started chipping away from that heroic image was seeing the attitudes of some of my fellow soldiers beginning to distort. And the racism, which is always bubbling below the surface in American society, started to boil over. To hear first the casual, "rag-head" and "hadji" becoming common. And then to hear that Osama bin Laden is the head of Islam, or that Muslims and Islam were two different religions. The ignorance and xenophobia became expressed in the way that some of the soldiers treated Iraqis. And when I saw guys who I considered basically good human beings, putting their rifle in the face of stranger just because he was a Muslim, or hitting a child with a steel Humvee antenna just because they were tired of them, I started to say, wait a second. I've been sold a bill of goods about this wholly heroic, wholly patriotic institution. The truth is this wasn't the case. And it's not because the people are inherently bad. It's the situation, which makes it untenable and puts such strain on people that it brings out our worst attributes.

RA: Do you have any thoughts on the connection between racism and war?

AD: It's crucial to our understanding of this war in particular. You can go back and catalogue every ethnic and racial slur that been used by American soldiers literally back to the Revolutionary war. It's a way people have of putting distance between themselves and the person on the other side. It's a way of making it acceptable to harm them. I can understand that from a psychological perspective. But in this war, it's different. The name calling, the "rag-heads," the "hadjis" began before we were in Afghanistan and Iraq. It began on September 11th. In my hometown of Tampa Bay, mosques were covered with blood and Muslim Americans were attacked. We have a large portion of Americans who believe that all Muslims and all Arabs are somehow connected to the terrorism of 911 – at least on some emotional level.

RA: So we transported our home-based racism to this war.

AD: Absolutely. And I don't want say that American soldiers are themselves inherently racist because of who they are – no, not at all. It's only that they transport whatever is in American society – the good and the bad – along with them. After 911 it became okay to look askance at Muslim Americans, to look sideways at someone speaking Arabic. Those are the things that gave rise to the brutality that is happening now.

RA: And if you are training someone to kill in war, you have to make sure that they aren't able to sympathize with anyone on the other side.

AD: That's part of the breakdown. It's no longer engaging a human being, it's engaging a target – an abstraction. This happened in basic training. The little target dummies used to be painted green with a red star on their cap, symbolizing Russian soldiers from the Cold War. Now they were calling them "Osamas," "Taliban," "rag-heads" – a quick transition from our old enemies to our new ones. It had already begun in basic training indoctrination- these people were less than us. And part of that is this horribly prolific lie that Muslims don't value life. I heard that repeated often. And you think, well, if they don't care about life, then I shouldn't care about their life.

RA: A big part of your experience was your emerging commitment to Buddhism at the same time you were going into this conflict.

AD: Yes. I had become a Buddhist shortly after enlisting partially in relation to the stress of going into the army, but I wasn't very serious. I was a Sunday morning Buddhist, if you will. But when I went to Iraq it really made me much more solid. My Buddhism and my conscious objection developed in tandem, because it was the experiences all around me that were driving home the truth of what Buddhism taught.

RA: Is there any part that you can share that will help people understand how that really emerged for you?

AD: There's so much. I'd really like to talk about this idea that killing is permanent-that if somehow we can find all of our enemies and kill them, then it will be over and we won't have any more enemies. But the truth is that by the very act of striking down someone, of killing a terrorist or killing an insurgent – you create more. Like the mythical Hydra, for every head you cut off, two more spring up in its place. Violence and hatred are counter-productive. For every unit we put into destruction and hatred, we will reap two units back. And this idea that the enemy can only be dealt with by aggression is so counter to a Buddhist understanding. There is a great Tibetan monk, Geshe Kelsang Gyatso, who once said, "Love is the only real nuclear bomb that is capable of destroying enemies." In other words, the only way to remove an enemy is to make him your friend.

RA: You actually turned in your weapon.

AD: I did. About the third month that I was in Iraq I had reached a crisis of conscious and morality. Internally I felt I was at a crossroads between being a fake Buddhist and being somebody who embodies and exudes Buddhism from every pore. So I went to my commander and turned in my machine gun and said, "look, I will stay, I will uphold my duty, but I will not fight and I will not kill because killing is wrong and war is wrong and I will not participate in that. I want to be processed as a conscientious objector." And thus I began the extremely long and arduous process of the CO application.

RA: How did that feel to be without a weapon?

AD: The moment before I made my declaration I was in utter turmoil. I knew I would suffer terrible consequences for upholding that belief – and yet, not upholding it would be worse. To lie in my bunk at night and to look up at the paint chipping on the ceiling, and to think about what kind of man I was and what war was making me was worse. To endure one more of those nights was greater than any other consequence I could suffer. And the moment I turned in my weapon I felt a wash of liberation. I felt free. The idea that no matter what happened I was upholding my belief – I was free.

RA: Was the vulnerability more freeing than the possibility that you could protect yourself?

AD: My commander took away my ballistic plates and my body armor as a way of coercion – to make me take back my CO application. But at that moment I felt guided by the hand of fate and the sense that upholding my belief was so crucial that anything else fell by the wayside. To be physically safe but morally in danger is more painful than the reverse.

RadioActive airs live M-F at noon on KRCL 90.9 FM. You can stream the entire interview at www.krcl.org.