In early 2012, something weird started to happen to my body. I’d never had the most steady health, but this was something new; I was completely, utterly exhausted, all the time. My muscles trembled with the slightest exertion, and my joints ached. Most of the time I was shivering cold, but occasionally I was running a mild fever. A combination of anxiety and depression left me with a constant impending doom, like some unseen giant was waiting to squash me like a bug. I started to have trouble swallowing, and I could no longer sing without coughing.

Editor’s note: January is Thyroid Awareness Month. CATALYST contributing writer Alice Toler tells her story of dealing with long-undiagnosed hypothyroidism (thyroid insufficiency) and the beginning of her journey back to wellness.

In early 2012, something weird started to happen to my body. I’d never had the most steady health, but this was something new; I was completely, utterly exhausted, all the time. My muscles trembled with the slightest exertion, and my joints ached. Most of the time I was shivering cold, but occasionally I was running a mild fever. A combination of anxiety and depression left me with a constant impending doom, like some unseen giant was waiting to squash me like a bug. I started to have trouble swallowing, and I could no longer sing without coughing.

I moved through a panoply of doctors’ offices. I gave blood for a million tests, had my liver and kidneys checked, pooped in a “plastic hat” to find out if I had parasites, and was examined for hidden bacterial infections. Nothing came back positive.

Over the next couple of years I put on close to 50 pounds and got out of shape, but paradoxically my resting heart rate kept dropping, as did my blood pressure. If I had errands to run, I saved up energy beforehand and cleared my schedule afterward so I would have time to recover. My ability to work slowly eroded away. I had to take a sabbatical from writing for CATALYST, because my brain just wasn’t up to organizing thoughts in a coherent fashion in text. Frankly, I felt like a bathtub with the plug pulled out—everything I did seemed to drain away to nothing, no matter what I did. I felt like I was slowly dying. Eventually I gave up trying to figure out what was going on. I resigned myself to my fate, whatever that might be.

Earlier this year, I was at a naturopath’s office having some treatment done on my gammy knees, and I mentioned my overall ill health. He gave me a sharpish look and said, “That sounds like you may have a problem with your thyroid.” I said “Oh, no, they tested my thyroid up at the hospital —they said it’s okay.” “I think they’re wrong,” he replied.

In short, he was correct. And I found out that the so called “gold standard” single-item thyroid test I’d been given earlier had, as it does for so many people, simply not shown my thyroid insufficiency.

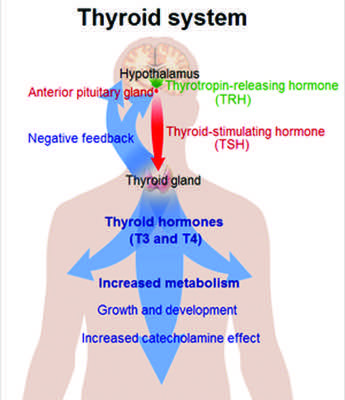

Western medicine tests for TSH, “thyroid stimulating hormone,” made by the pituitary gland, which functions like an order slip that a waiter (the pituitary gland) gives to a short order cook (the thyroid) at a diner. Normally, the pituitary asks the thyroid to make its own hormones, and when it does, the pituitary gets the message and quits asking. In some people who are hypothyroid, the TSH “order slips” start stacking up, because the thyroid isn’t responding to the pituitary —so a blood test for TSH will show high levels. However, in other people the TSH levels will appear “normal” when there’s a defect farther along the metabolic chain. Every single cell in your body requires adequate amounts of usable thyroid hormone to function, so if you aren’t getting enough, you’ll feel pretty awful, just like I did.

My naturopath put me on “natural desiccated thyroid”—little brown pills made out of pig thyroid – and I started a regimen of thyroid-supporting supplements (see sidebar). It took two months before I started to feel any better, and when I did, I was almost afraid it would turn out to be a transient effect, or some kind of illusion. Thankfully it was neither, and my health finally started to really improve by September of last year.

The personal landscape of “thyroid issues” is crazy-making on many different levels. Firstly, if your brain cells aren’t getting enough thyroid hormone to function properly, you will literally not be able to think. Additionally, the symptoms of hypothyroidism can be so nonspecific that sufferers are very often simply misdiagnosed with depression or anxiety, and put on psychiatric meds, which have limited efficacy in this sort of case.

Even if you’re correctly diagnosed, it doesn’t necessarily get any easier. Most doctors don’t know that much about thyroid metabolism—it’s fiendishly complicated—and they’ll go by the book and prescribe a synthetic “T4-only” hormone replacement drug that doesn’t work for people with thyroid hormone conversion problems like myself.

Furthermore, because most doctors only look at the TSH number, they will tell you you’re “cured” of hypothyroidism after you’ve been taking whatever medication, and decrease your dose or take you off it, even if doing so makes your symptoms come back or worsen.

On top of all of this, it’s common for people with hypothyroidism to also be suffering with adrenal insufficiency or any of a number of vitamin and mineral deficiencies, all of which need to be addressed one way or another before you start feeling well again.

I am somewhat lucky. I had already been working on my adrenal problems and my low Vitamin D levels for a couple of years before I was diagnosed hypothyroid. I’d also given up eating processed foods long ago. I was not as far behind the eight-ball as I might have been.

As I read and researched more, however, I began to realize that there is an enormous population of hypothyroid people who aren’t being served adequately by the medical profession. I found knowledgeable and compassionate support among a community of tens of thousands of thyroid patients who have been crowdsourcing information to understand their own endocrine issues. A notable website is “Stop The Thyroid Madness,” and there are several Facebook support groups as well (“For Thyroid Patients Only” is a good example). Everyone’s metabolism is different, and everyone’s thyroid problems are unique, but the members of these communities can offer some good starting point.

You have to be your own advocate. If you think you may have hypothyroidism, or if you are diagnosed hypothyroid and on meds and still suffering symptoms, I can only encourage you to learn as much as you possibly can about your own body, and to seek out a doctor who will treat your symptoms and not just your lab numbers.

I am no doctor, much less an endocrinologist, but I believe that we each have the power to take charge of our health by learning what’s going on in our bodies. It may be an enormous task, but as my mother always says, “If you don’t have your health, you don’t have anything,” so you might as well begin.

Funky Thyroid: What goes wrong?

When the thyroid goes wacky, the body can’t control its metabolism and loses immune function. Three main types of disease affect this butterfly-shaped gland at the front of your throat:

When the thyroid goes wacky, the body can’t control its metabolism and loses immune function. Three main types of disease affect this butterfly-shaped gland at the front of your throat:

Hypothyroidism:

When your thyroid is underactive, or when your body’s cells aren’t able to absorb thyroid hormone properly. Symptoms: fatigue, swelling, weight gain, constipation, infertility, low body temperature, inability to think clearly, depression, anxiety, menstrual irregularities, sleep disturbances, joint and muscle aches, hair loss (particularly the outer regions of the eyebrows), difficulty swallowing, hoarseness, light sensitivity, numbness, dry skin.

Women are far more likely to be diagnosed with hypothyroidism than men. Hypothyroidism is implicated in infertility, miscarriage, endometriosis, polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), PMS, uterine fibroids and low libido.

Hashimoto’s Disease:

When the immune system attacks the thyroid. Symptoms: largely the same as those of non-Hashimoto’s hypothyroidism, but the treatment may be include avoiding certain supplements that are beneficial to people with non-Hashimoto’s hypothyroidism. Lab testing for thyroid antibodies in the blood is vital for diagnosis.

Hyperthyroidism:

An overactive thyroid that is putting out too much hormone. It can be genetic or caused by inflammation or an autoimmune condition. Symptoms: sudden weight loss, increased appetite, irritability, anxiety, panic attacks, increased sweating, diarrhea, difficulty sleeping, fatigue and muscle weakness, an enlarged thyroid (goiter) on the neck, bulging eyes, irregular menses, rapid or irregular heartbeat.

Be Nice to Your Thyroid

DE-STRESS

The number one thing you can do for your thyroid is to manage your stress levels. When you remain in a state of high anxiety, it unbalances your endocrine system. Take time for self care! Mindfulness and meditation can help a lot, but there is no substitute for learning to set healthy boundaries.

SLEEP

Sleep is extremely important. Poor sleep can be a sign of both an underactive or an overactive thyroid.

EXERCISE

Yoga is a great thyroid-boosting exercise, but pretty much any way you choose to move your body will help. When you exercise, your body releases endorphins which make you feel better. Take a class or just walk the dog, but make sure you get yourself moving every single day.

DIET

Gut health is key. In general, a diet of healthy, non-processed foods will support your thyroid well. However, there are some specific foods that act on the thyroid that you may want to seek out or avoid:

Seek out: Healthy fats, eggs, saltwater fish, brazil nuts, mushrooms, pumpkin seeds, and dairy if you can tolerate it. All of these foods contain selenium and iodine, and will support thyroid function.

Avoid: Sad but true, if you have thyroid issues, kale and its cruciferous kin (cabbage, broccoli, bok choi, daikon, cauliflower, collards) may not be your best friend. They contain chemicals called goitrogens that interfere with thyroid function. Other goitrogenic foods include soy, pine nuts, peanuts, flax seeds, strawberries, pears, peaches, spinach and sweet potatoes. (If you do eat them, cook them first.)

Also avoid gluten, caffeine, sugar and other refined carbohydrates.

SUPPLEMENTATION

Before embarking on any regimen of supplements, please consult with your healthcare provider.

In general, the thyroid needs iodine. If you have given up processed foods and use sea salt instead of iodized salt in your cooking, you may not be getting enough iodine. This is easily remedied with kelp tablets or a drop of Lugol’s iodine in water twice a week. However, if there is even a slight chance you may have Hashimoto’s disease, taking iodine can accelerate the destruction of your thyroid—so make sure you have talked to your doctor and had blood tests for thyroid antibodies first.

Selenium is particularly vital for good thyroid and immune system function. If your gut health has been poor, or if you have chronic inflammation, you may not have been able to absorb selenium from your diet. Selenium is vital for the conversion of the cell-inactive T4 thyroid hormone to the active T3 version, so optimal selenium is very important.

Many hypothyroid patients are deficient in vitamin D. This important vitamin regulates insulin secretion, balances blood sugar, and balances the immune system. High cortisol levels (i.e. chronic stress) can eat away at vitamin D levels, as can poor gut health, obesity, and a diet too low in fat. If you have low thyroid function, it’s possible that you may experience the effects of vitamin D deficiency even if your blood levels of vitamin D are in the “normal” range, so you will want to work with your doctor to figure out the right level of supplementation for you.

Omega 3s are even more important for thyroid patients than the normal population. They help decrease inflammation and boost the immune system.

L-tyrosine is required for the thyroid to make its hormones. Be careful of this supplement if you are taking thyroid hormone medication.

Zinc, copper and iron may also be deficient, and some people with thyroid problems may also not be able to absorb B vitamins properly. Vitamin K2 has been shown to be useful, unless there’s a blood clotting problem.

Alice Toler is a regular contributor to CATALYST, as both a writer and artist. We are so glad she is feeling better!