Rather than simple promiscuity, polyamorists claim a more complex desire: to create and maintain honest, consensual, ongoing, loving relationships with more than one person.

The term “non-monogamy” is appearing more regularly in the press and in the national dialogue. A catch-all reference for relationships that can involve sexual intimacy with more than one partner, non-monogamy manifests in several ways. Utahns, of course, were aware of polygamy long before “Big Love” and “Sister Wives.” “Swinging,” with its partner swaps and often anonymous, recreational, and temporary sexual hookups, has been grist for books and films since the ’50s. Despite Utah’s ultra-conservative reputation, an underground sub-culture of swingers continues to thrive here. Those drawn to polyamory, however, claim a more complex desire: to create and maintain honest, consensual, ongoing, loving relationships with more than just one other person.

The word polyamory entered the modern lexicon in 1990, the mixed Greek/Latin roots meaning “to have many loves.” But it’s not a recent phenomenon. Several books written in the past two decades report many combat pilots and their wives during World War II practiced a form of it. So did their commander-in-chief—Franklin D. Roosevelt and his wife, Eleanor, who both maintained outside love interests that were known to the other.

In certain cultures throughout human history, something akin to polyamory has actually been the norm. According to a July 29, 2009 Newsweek online report, as many as half a million American families are openly polyamorous (tinyurl.com/29qklbp). Even if that figure is correct, however, most people whose lifestyle could be labeled polyamorous remain below the public radar.

They may live together or not; see each other frequently or rarely; be straight, gay, bisexual or some variation. However, even though it’s been a feature of Western civilization since the Roman Empire, they all defy the idea that monogamy is the only model for marriage and relationships.

I am ethically bound to share with you my own experience and situation: I left a conservative religion and 30 years of monogamy in 2004. I have lived for almost four years now with a “primary partner.” The relationship is polyamorous on my account; my partner is monogamous.

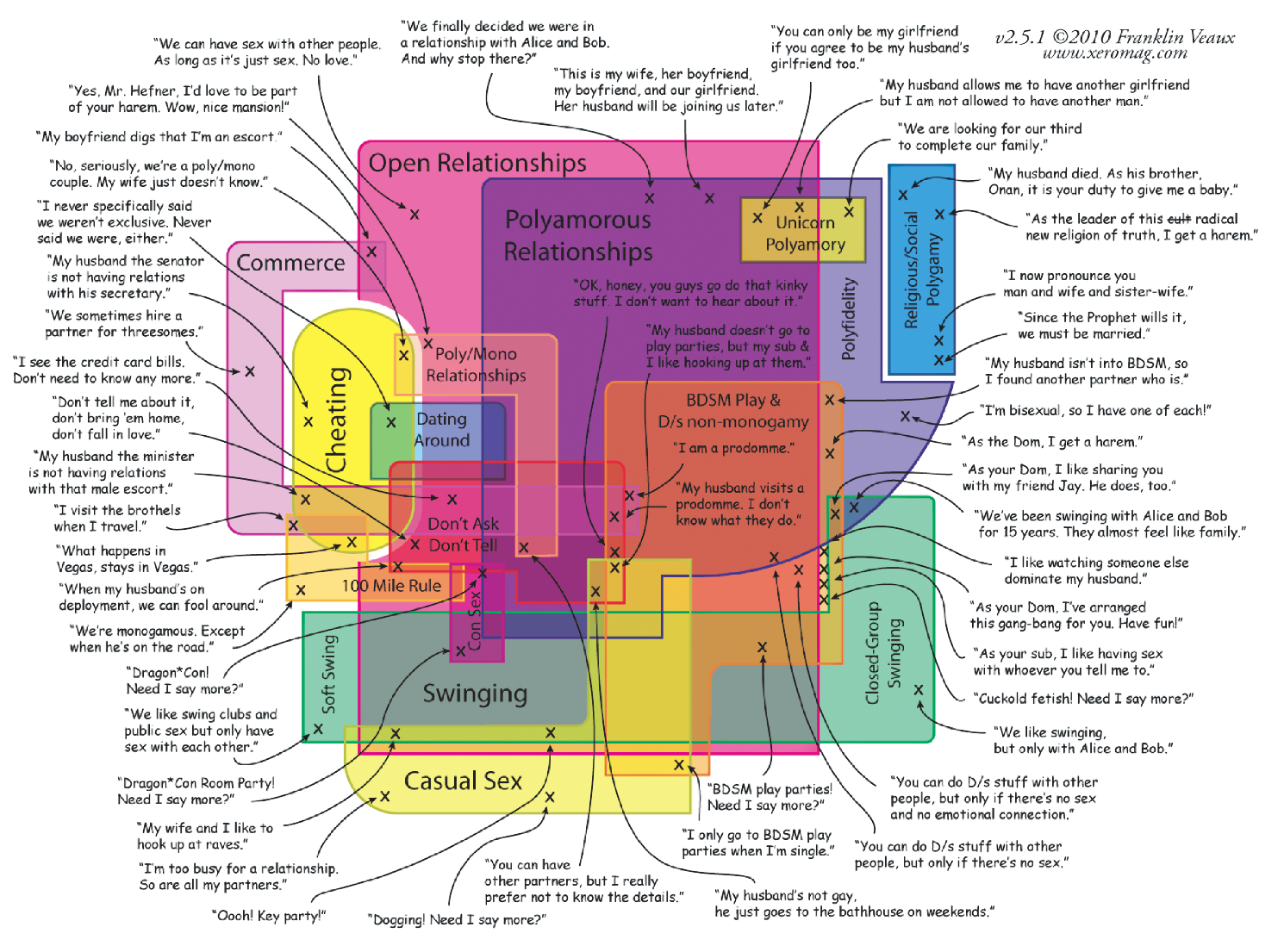

Differentiating polyamory among the various non-monogamous arrangements can be tricky. Deceptive cheating while pretending to be monogamous is a form of non-monogamy that most people hold in low regard. In another form, one partner reluctantly tolerates the dalliances of the other. Moving up the integrity scale, partners in some open relationships maintain a “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy—both are free to discretely do their own thing but not become emotionally attached to their outside interests. Franklin Veaux’s Venn diagram graphic (see opposite page) makes a valiant attempt to illustrate all the various types of non-monogamous arrangements even including a “commercial” category for prostitution.

But people who identify their relational style as polyamorous do something most other non-monogamists often don’t. Less interested in quick hook-ups primarily for diversion, polyamorists often become, to some degree, part of each others’ lives. Unlike polygamy, polyamory tends more toward gender equality, with women having as much sexual freedom as men. There is also the intention to feel positive about a partner’s other relationships.

As liberal (or libertine) as all this seems, polyamorous relationships don’t necessarily involve group or even more sex. Most polyamorists prefer the intimacy of one-on-one encounters with each of their partners. Some practice polyfidelity—everyone staying sexually within a well-defined group. Others practice fluid bonding—using condoms or other protection whenever they have outside contact and with everyone’s sexual history verified by STD testing.

Who’s doing it?

Much of the recent national media coverage of polyamory has been positive or at least inquisitively neutral. Historically, quirky literary and artsy non-monogamists such as Ayn Rand and Anais Nin have been socially tolerated just as actress Tilda Swinton and Hollywood couple Will Smith and Jada Pinkett-Smith are today. What’s bigger news is the polyamorous lifestyle of seemingly buttoned-down, establishment-types like America’s second wealthiest person and philanthropist Warren Buffett.

Despite thawing public disapproval, many still encounter subtle to serious objections from family, friends, employers and public officials. More than one former spouse has used an ex’s polyamorous lifestyle to win a child custody case. Others have found themselves suddenly unemployed when they were outed. Understandably, many keep their situations confidential.

Of course, just as in monogamous ones, the toughest challenges come from within poly relationships themselves. Poly people have to face the green-eyed monster of jealousy just like anyone else—perhaps even moreso, and actually being pleased about a lover’s other lover doesn’t come naturally for most. Life can become especially challenging during new relationship energy—the stuff that gets generated during the giddy phase of a budding relationship and can be threatening to partners in established relationships that have become less romantic and more comfortable.

Our culture trains us to be possessive about romantic partners; love is considered finite in quantity. Polyamory stretches the paradigm, claiming that love for more than one other person is like a parent’s love for more than one child—it just develops when they show up, and it doesn’t get diluted as it expands. The more the merrier—up to a point.

Wired for promiscuity

Where does the urge to have more than one partner originate? Is it a deviant sexual orientation? An overactive libido? Emotional and mental instability? The result of a moral or spiritual defect? Or could it be basic to human beings?

In Sex at Dawn: the Prehistoric Origins of Modern Sexuality, psychologist Christopher Ryan and psychiatrist Cacilda Jetha point out that Western society inherited monogamy from the Romans—an institution created mostly to determine inheritances. The Romans, however, and especially those of the upper class, were hardly monogamous in practice. The expectation of sexual exclusivity came later, after the merger of the Empire and Christianity in the fourth century.

Both monogamy and polygamy have their roots in the rise of agrarian societies about 10,000 years ago. When humans transitioned from being foraging gatherers and hunters to herders and farmers, land went from being a shared resource to private property, and exclusive marriages were created to transfer accumulated wealth to heirs. In societies that featured more competition between males, polygamy became the norm with its one-man-take-most theme. In less competitive cultures, monogamy arose.

Ryan and Jetha argue that we don’t appreciate the manner in which humans interrelated for the first roughly 200,000-plus years of our existence. Foragers lived in relatively small, highly interdependent groups that had little hierarchy, almost no competition among members, and featured more equality between the sexes. Such social dynamics continue today among remote tribal peoples, and various forms of non-monogamy are still common, especially in groups that have little contact with the West. Polyamory may have simply been the norm among our ancestors.

The authors cite the research of scientists who study human anthropology and our closest evolutionary cousins, the bonobo chimpanzees which share 98.4% of our DNA, and conclude that we’re fundamentally wired for…I wish there were a less loaded term…promiscuity. As evidence, human males are only slightly larger than females, a common trait in promiscuous primate species.

Among polygamous gorillas, on the other hand, males are more than twice the size of females—a trait that developed to be able to better fight off male rivals.

Human women, unlike the females of the purely monogamous or polygamous primate species, may experience sexual arousal regardless of where they are in their menstrual cycle and desire sexual activity as much as men especially in sexually unrepressed societies. The high sex drive of both men and women goes far beyond what’s needed for reproduction—an odd trait which evolution wouldn’t have created unless sexual intimacy serves a purpose beyond procreation.

In “primitive” polyamorous societies, these authors contend, it doesn’t matter whose sperm does the impregnating although studies show that women, even in more “civilized” societies, prefer the attention of men they consider most physically desirable during the fertile phase of their cycle. However, children are an asset to the entire group and are raised by all in cultures without the rigid nuclear family boundaries of monogamous Western society.

Among our promiscuous bonobo cousins, sex is like social glue, and almost all members of a troop regularly engage in it with the other mature bonobos. Biologists and animal behaviorists contend that sexual interaction is essential to their high degree of group interdependence and cohesion. Ryan and Jetha assemble ample evidence that that’s how humans are wired, too, suggesting that possessiveness and jealousy are the real modern perversions.

They argue that Darwin was influenced by Victorian social values when he concluded that competition among human males for females was counterproductive and resulted in evolution settling the dispute by creating monogamous coupling. It wasn’t the first time he dodged a controversy to avoid aggravating influential, pious churchmen and financial benefactors and to minimize the anxiety his views often caused for his adored wife, a devout Christian.

No need to lie

So what does this mean for modern polyamorists willing to wave off modern social conventions and explore their ancient biological and psychological programming? Poly-inclined friends don’t have to twist themselves into anxious knots if a sexual attraction starts to blossom. They may not move in together, but they have the option of guiltless “friends with benefits” arrangements and taking those relationships to whatever level of involvement is comfortable for all parties.

Unfaithfulness now affects over half of all monogamous marriages and long-term relationships, but if poly folk honor agreements made with their partners and are open about who is spending time with whom, they don’t fall victim to infidelity and the deception that surrounds it. When the seven-year itch (or the four-year variant that modern researchers identify as the more critical juncture) or even a six-month urge to wander strikes, polyamorists aren’t compelled to subconsciously subvert their otherwise viable existing relationships to clear the way for a new one. Polyamory offers an alternative to serial monogamy—the current less-than-happy norm in Western society. Poly partners and spouses don’t choose between sexual novelty and long-term stability. They enjoy both.

Any experienced polyamorous person will admit that this love style is definitely not for everyone and is never a cure for an already failing relationship. A troubled couple rarely finds relief simply by adding more people to the mix.

However, for those not intimidated by the idea of moving beyond social conventions and their own insecurities, and who have the time and energy to be with more than one intimate partner, polyamory may open up a world of enlivening new possibilities.

Where to turn

For those pushing against all the cultural momentum flowing in the opposite direction from friends, family members and society’s institutions, resources and outside support are available. Several books address the personal, family, work, social and legal issues involved.

The Ethical Slut (1997, revised 2009), by Dossie Easton and Janet W. Hardy. The groundbreaking classic text for polyamorists.

Opening Up (2008), by Tristan Taormino. Perhaps the most popular how-to guide—the fruit of interviews with almost 200 polyamorists describing why they’ve adopted the lifestyle and how they deal with its challenges. An online polyamory “bookshelf” is at listal.com/list/polyamory-books.

Lovemore.com. A national network of polyamorists focused on education and advocacy, headed by Robyn Trask, editor of Loving More Magazine. In addition to the monthly periodical, her organization hosts national, educational and support conferences.

Utah Polyamory Society

Listserv at groups.yahoo.com/group/UtahPolyamorySociety. Over 500 subscribers, hosts meetings twice a month with occasional socials for typically 10 to 100 attendees. To be clear, these are not sex parties, and visitors with a prurient curiosity are disappointed by the generally serious tone. Participants come to learn about the poly lifestyle or for advice to live it successfully.

Booklists, personal ads, and discussion forums:

xeromag.com/fvpoly.html, polyamory.com, polymatchmaker.org. Others such as OKCupid (okcupid.com) are “poly friendly.”

Freelance writer and editor Jim Catano’s other life involves the launch of two ultra-progressive, health-related projects.

http://issuu.com/catalystmagazine/docs/catalyst_1103/16