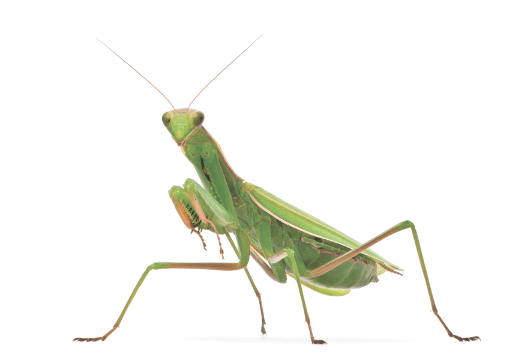

Creating beneficial insect habitat: Lacewings, lady bugs and mantis, oh my!

—by James Loomis

Now, this is not another article about bees, or any other pollinators for that matter. Bees get entirely too much press when it comes to insects in the garden. Bless their little honey-crusted hearts, but there’s a whole other cast of characters that deserve a little time in the limelight. This is an article about a voracious crew of blood-thirsty assassins, hellbent on keeping pest populations to a minimum: predatory insects.

I’m fond of repeating the mantra, “There are no pest problems, only a lack of predators.” In a balanced ecosystem, predators and their prey tend to reach an equilibrium in their respective populations. When we achieve this balance in the garden, the result is that we see very little sustained damage from pests. The occasional infestation may pop up, but before you have time to worry, they’re gone, a feast for our good guy insect allies. Unfortunately, most gardens are severely lacking in beneficial insects, and this is generally caused by one of two things; the use of broad spectrum insecticides in the garden, or a lack of the habitat needed to sustain a healthy beneficial insect population.

I’d like to point out that the slaughter of beneficial insects often occurs even in “organic” gardens and farms. In USDA Organic agriculture, it is prohibited for the grower to spray broad spectrum insecticides made from petrochemicals, yet it is entirely acceptable to use insecticides made from flowers. (Pyrethrins, which can be made from the chrysanthemum flower, fit this description). While slightly less toxic to people and planet, these broad-spectrum organic insecticides still kill indiscriminantly, and even the occasional use of these products will disrupt the balance we are seeking with our insect populations. It’s nearly impossible to wipe out an entire pest population, and they tend to repopulate rapidly. Conversely, our beneficial insect population tends to breed much slower than the pests, so by using insecticides we end up favoring pest insects in our garden.

By avoiding wholesale slaughter of insect populations, we allow the numbers of our beneficial insects to build up to control levels. Once a healthy balance is achieved, pest populations can be constantly suppressed. Rock the boat with pesticides, and it’s back to square one. This is a longterm solution, and it will take time for balance to be achieved. Be patient, quick fixes are almost always temporary. Every time you reach for an insecticide, organic or conventional, you are actually making the problem worse, and increasing your dependency on the product. Furthermore, these products are harmful to the microbes on the plants and in the soil as well, which further weaken the resiliency of our garden ecosystem. I’m not saying you’re an a**hole for using insecticides; wait, yes I am. That’s exactly what I’m saying. Stop using them.

Once we’ve committed to not killing our beneficial insects, we can focus on attracting and sustaining their presence in our gardens. A simple equation to accomplish this is Food + Water + Shelter = Sexy Time. Provide the first three and your beneficial insects will stick around and breed, and you’ll have a self-sustained population of beneficial insects.

Reminder: When in doubt, don’t kill a bug! A general rule of thumb is that most pests occur in clusters, and most beneficials are somewhat more solitary. Learning to identify and spot beneficial insects can add another layer of enjoyment and action in your garden. In a future column I’ll help you learn to identify the various stages of our generalist predators, as well as their eggs.

Now get outside and grow!

Habitat basics

Without sufficient habitat in place, any purchased insects will fly off in search of a better home. One of my favorite instructions that I’ve seen accompany a bucket of ladybugs advises the consumer to “spray the ladybugs with 7-Up diluted with water. The sticky residue will glue their wings closed and they won’t be able to fly off for several days.” Seriously? That’s the opposite of a boss move. A better strategy, savvy gardener friend of mine, is to plant the proper habitat; then, all of the purchased ladybugs from your neighbors will take up residency in your garden. That’s a boss move. Nice work.

Without sufficient habitat in place, any purchased insects will fly off in search of a better home. One of my favorite instructions that I’ve seen accompany a bucket of ladybugs advises the consumer to “spray the ladybugs with 7-Up diluted with water. The sticky residue will glue their wings closed and they won’t be able to fly off for several days.” Seriously? That’s the opposite of a boss move. A better strategy, savvy gardener friend of mine, is to plant the proper habitat; then, all of the purchased ladybugs from your neighbors will take up residency in your garden. That’s a boss move. Nice work.

So what is sufficient habitat? In my designs, I shoot for a bare minimum of around 15-20% of available space devoted to a mix of perennial and annual plants that serve the primary purpose of providing habitat and nectar for the good bugs on your team. Most of the generalist insect predators we are trying to attract, such as lacewings, syrphid flies, aphid midges, and ladybugs, feed primarily on nectar as adults. It’s their larval stages that wreak havoc on clusters of aphids and other pests. In order to get a steady supply of these gangster insect youth, we need to keep the adults around and well fed.

Remember, one of the most important strategies to embrace is diversity. We want to make sure to have a diversity of plant height, flower size and color, and bloom time. Making sure there are always multiple plants in bloom not only makes for ideal habitat, it also results in a more beautiful garden.

Food

When choosing food plants for our beneficial insects, consider the size of their faces. Larger blossoms tend to attract bees, moths, and other pollinators, while tiny blooms tend to attract our generalist predators. In particular, think “big clusters of small flowers.” Most of our predatory insects prefer plants with large clusters of micro flowers. My staple in this application is sweet alyssum, a prolific, easy to care for plant that puts out copious amounts of flowers in a matter of weeks after it emerges, and keeps cranking them until it freezes. There is also a perennial Alyssum, which adds to the diversity. Yarrow, another great staple, is low maintenance and requires little water. Buckwheat comes up and flowers fast, which is great for getting cover in quickly (and is also my favorite cover crop for weed suppression). Clovers are also fantastic, and make a great living mulch below taller crops, which is a great trick for tucking in that 20% minimum into your design. This is a classic permaculture design concept known as “stacking functions”

When choosing food plants for our beneficial insects, consider the size of their faces. Larger blossoms tend to attract bees, moths, and other pollinators, while tiny blooms tend to attract our generalist predators. In particular, think “big clusters of small flowers.” Most of our predatory insects prefer plants with large clusters of micro flowers. My staple in this application is sweet alyssum, a prolific, easy to care for plant that puts out copious amounts of flowers in a matter of weeks after it emerges, and keeps cranking them until it freezes. There is also a perennial Alyssum, which adds to the diversity. Yarrow, another great staple, is low maintenance and requires little water. Buckwheat comes up and flowers fast, which is great for getting cover in quickly (and is also my favorite cover crop for weed suppression). Clovers are also fantastic, and make a great living mulch below taller crops, which is a great trick for tucking in that 20% minimum into your design. This is a classic permaculture design concept known as “stacking functions”

We can take this whole stacking functions party up a notch by cultivating plants we can use before they flower, like dill, parsley and cilantro, which, like aphids to insects, are delicious to people. These plants can be harvested continually as they grow, and once they bolt, ka-pow! Big clusters of small flowers. Dill in particular is a one stop shop for the action; aphids are drawn to it, and ladybugs love it, too. Attract the pests, attract the solution. Genius. Thanks, Momma Nature, you’re the ultimate boss.

Let’s keep going, and step this thing up one more time. Most of our spring crops produce these large clusters of small flowers when they “bolt,” or set seed. Let some of your lettuce, arugula, and brassicas flower to provide food for our beneficial insects, and then harvest their seed once mature. Food for you, then nectar for insects, then seed for next season, all from the same square foot. Stacking functions at its finest, seriously next level boss maneuver.

James Loomis is a “Beyond Organic” grower, farm consultant, and mentor. He teaches workshops on a variety of topics related to regenerative agriculture. Facebook.com/beyondorganic